Davy Lamp

The Davy lamp, credited with saving thousands of lives, was freely given to the world by its inventor without seeking a patent.

Source: by Stable MARK - own work, own collection.

This article explores the invention, working principle, impact, and legacy of the Davy lamp, including rare visuals and original experiment reconstructions.

Table of Contents

What is the Davy lamp used for?Who Invented the Davy Lamp?How Do Davy Lamps Work?When Was the Davy Lamp Invented?Experiments That Led to the Invention of Davy LampLamp Variants and ImprovementsWas the Davy Lamp Perfectly Safe?Is the Davy Lamp Still Used Today?How Many Lives Did the Davy Lamp Save?Parliamentary Reports on Safety Lamp LimitationsNegative Consequences of the Davy LampDavy Lamp DrawingsWas It Davy or Stephenson Who Invented the LampWhat Is the Difference Between a Davy Lamp and a Geordie Lamp?The Davy lamp is a type of safety lamp invented in 1815 by the chemist Sir Humphry Davy. Designed for use in coal mines, it safely illuminated flammable environments without igniting the deadly gases underground, such as methane (also called firedamp).

Source: Stories of Inventors and Discoverers in Science and the Useful Arts. A book for Old and Young. By John Timbs, F.S.A., Google Books

What made the Davy lamp revolutionary was its use of a fine wire gauze to enclose the flame — preventing explosions while still allowing light and airflow.

What is the Davy lamp used for?

The Davy lamp was created to provide safe lighting in coal mines, where dangerous gases like methane (firedamp) were commonly found. Before its invention, miners relied on naked flames, which often triggered deadly explosions.

Source: Popular Science Monthly, Google Books

With its protective wire gauze, the Davy lamp allowed miners to carry light underground without igniting flammable gases — making deep mining safer and more productive.

Source: Pages Weekly - 1902, Google Books

Learn More Still curious? Click here to learn about the Miners lamps.

Paraffin Lamp British Coal Miners Company Wales UK Aberaman Colliery Oil Lantern with Hook

Who Invented the Davy Lamp?

The Davy lamp was invented in 1815 by Sir Humphry Davy, a British chemist. He created it to protect coal miners from deadly explosions caused by firedamp (methane gas). His design used metal gauze to surround the flame, making it safe to use in flammable environments.

Source: Mining an Elementary Treatise on the Getting of Minerals by Arnold Lupton, M.I.C.E, F.G.S., etc. - 1896,. Google Books

Before Davy, others had tried to solve the problem of underground gas explosions. William Reid Clanny designed a cumbersome safety lamp in 1813 that used water and glass, and Alexander von Humboldt had proposed flame-resistant lamps earlier in Germany. Their work helped set the stage for Davy’s more practical and scientifically refined design.

How Do Davy Lamps Work?

Source: Popular Sciense Monthly, Google Books

The Davy lamp works by surrounding the flame with a fine wire gauze, which allows air to reach the flame but prevents it from igniting explosive gases like methane outside the lamp. The gauze absorbs heat, cooling any flame trying to escape.

Source: Popular Sciense Monthly, Google Books

If dangerous gases are present, the flame burns higher or changes color, giving miners a warning. If oxygen is low, the flame goes out—another safety signal.

When Was the Davy Lamp Invented?

The Davy lamp was invented in late 1815, during an intense period of experimentation by Sir Humphry Davy. It was first tested successfully on January 9, 1816, at Hebburn Colliery in North East England.

Source: The Wonders of Science or, Young Humphry Davy by Henry Mayhew - 1856, Google Books

Before that, on November 3, 1815, Davy’s private letter describing his experiments was made public in Newcastle. He then formally presented his invention to the Royal Society in London on November 9, 1815, and was awarded the prestigious Rumford Medal for his work.

Vintage Oil Lamp British Coal Miners Company Wales Paraffin Miners Lantern with Hook

Experiments That Led to the Invention of Davy Lamp

Before finalizing his design, Davy carried out a chain of experiments:

Ether Vapour and the Glowing Platinum Coil

Can ignition be sustained without an open flame?

Source: The Wonders of Science or, Young Humphry Davy by Henry Mayhew - 1856, Google Books

Davy placed a red-hot platinum coil above a small amount of ether in a glass. As the ether vaporized, the coil kept glowing bright red without a visible flame. This showed that ignition could be maintained by heat alone — a critical insight for developing a flame-free safety lamp for miners.

Flame-Free Combustion with Spirit-Lamp

Can ignition be sustained after the flame is removed?

Source: The Wonders of Science or, Young Humphry Davy by Henry Mayhew - 1856, Google Books

Davy wrapped a red-hot platinum coil around the wick of a spirit-lamp filled with alcohol (spirit of wine). After lighting the lamp briefly, he snuffed out the flame—yet the coil kept glowing. The vapor continued to burn slowly on the hot metal alone, proving that visible flame wasn’t necessary to maintain combustion in certain conditions.

Is a Flame Alight in the Middle?

What part of a flame actually burns?

Source: The Wonders of Science or, Young Humphry Davy by Henry Mayhew - 1856, Google Books

To find out whether a candle flame burns at its center or just around the outside, Davy placed a thin glass plate directly onto the flame. Through the glass, he observed a bright ring with a dark central spot—proving the center of the flame contains unburnt gas due to lack of oxygen.

Testing Gases Inside the Flame

Source: The Wonders of Science or, Young Humphry Davy by Henry Mayhew - 1856, Google Books

To examine whether the dark center of a candle flame contained unburnt gases, Davy inserted a small glass tube into the middle of the flame. The gas rose through the tube, and when he brought another flame near the tube’s top, it ignited—producing a second flame. This proved that the central part of the flame held flammable gases that hadn't yet combusted.

The Concentric Tubes Experiment

Source: The Wonders of Science or, Young Humphry Davy by Henry Mayhew - 1856, Google Books

To prevent explosions caused by flame traveling through gas tubes, Davy began experimenting with smaller metal channels. He inserted fine metal tubes, one inside another, forming concentric rings with narrow air gaps between them. This setup allowed air to reach the flame but stopped the flame from passing back through. The experiment, shown in the image (7.jpg), proved that reducing the diameter of the tubes made the system safer. Davy then used this configuration at both the top and bottom of a lamp chimney, ensuring that even if firedamp entered the lamp, it wouldn’t ignite the surrounding air.

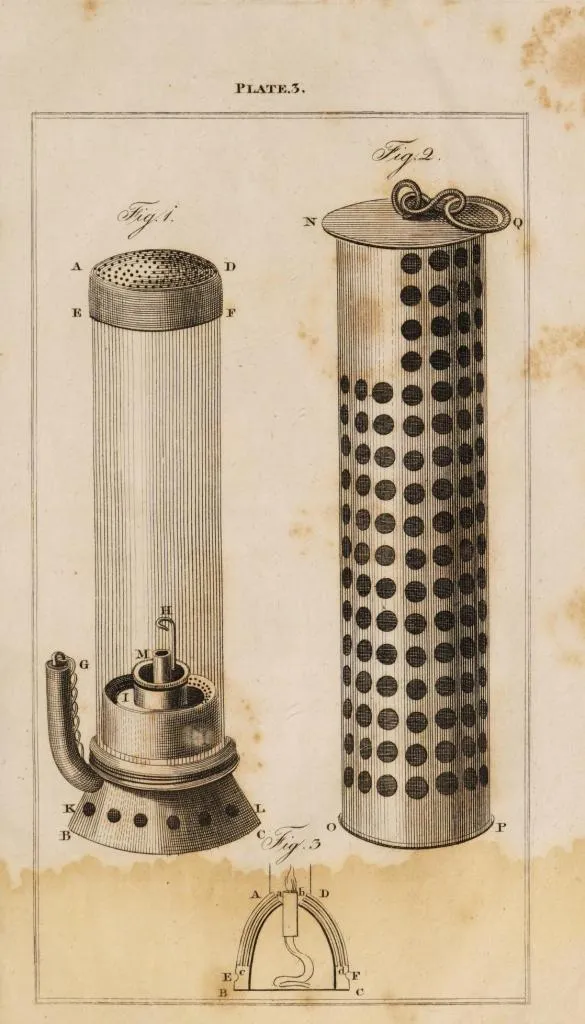

Design of the First Davy Safety Lamp

Source: The Wonders of Science or, Young Humphry Davy by Henry Mayhew - 1856, Google Books

In one of his final experiments, Davy assembled a prototype safety lamp using concentric metal tubes to manage airflow. He tested its reliability by immersing it in a highly explosive mix of gases. The flame inside could not ignite the gases outside, and if the firedamp entered, the flame was extinguished instead of causing an explosion. This confirmed the lamp’s safety.

Wire-Gauze Flame Test

In this experiment, Davy demonstrated how wire-gauze could stop the spread of flame. A flame was placed beneath a sheet of metal gauze. The flame passed through the gauze but did not ignite anything on the other side.

Source: The Wonders of Science or, Young Humphry Davy by Henry Mayhew - 1856, Google Books

Then a small piece of camphor was laid on the gauze, and a light held beneath it. The camphor vapour ignited and burned downwards, yet the camphor itself did not catch fire.

Source: The Wonders of Science or, Young Humphry Davy by Henry Mayhew - 1856, Google Books

These experiments proved that the metallic threads of the gauze, being excellent conductors of heat, absorbed enough energy to cool the flame and prevent it from spreading. This principle became central to the Davy lamp’s safety mechanism.

Final Design of The Safe-Lamp

Source: The Wonders of Science or, Young Humphry Davy by Henry Mayhew - 1856, Google Books

Davy’s final breakthrough was the realization that enclosing a flame within a fine wire-gauze cylinder would prevent the flame from escaping. Thanks to the cooling effect of the metallic mesh, even if explosive gases entered the lamp, they would burn safely inside without igniting the dangerous atmosphere outside. This simple yet brilliant design became the defining principle of the Davy safety lamp.

Lamp Variants and Improvements

Source: Mining an Elementary Treatise on the Getting of Minerals by Arnold Lupton, M.I.C.E, F.G.S., etc. - 1896,. Google Books

After perfecting the principle of the wire-gauze flame arrestor, Davy explored various lamp constructions to maximize safety and visibility. Some models had a glass shield around the gauze (like the Jack Lamp), others extended the glass chimney to the top, and some enclosed the entire flame in a solid outer case. Each version was adapted for specific mining conditions, balancing protection from explosive gases with practical lighting needs.

Was the Davy Lamp Perfectly Safe?

No, the Davy Lamp was not perfectly safe, even though it was a major improvement in mine safety.

Source: The Mine Foreman's Handbook by Robert Mauchline - 1910, Google Books

Why it wasn't completely safe:

- Mesh overheating: If the lamp was exposed to high levels of flammable gas (firedamp), the wire gauze could become red-hot. Once it reached that temperature, it could ignite gas outside the lamp, defeating the safety purpose.

- Airflow obstruction: Dirt, oil, or poor maintenance could block the gauze, causing the lamp to burn improperly or go out — or worse, let flame escape.

- Fragility in practice: Though more robust than the Geordie lamp, it was still vulnerable to rough handling. A damaged gauze made it ineffective and dangerous.

- Miners misunderstood its limits: Some miners believed the lamp could protect them no matter what, and would take it into gas-heavy areas without proper ventilation — a fatal mistake.

Is the Davy Lamp Still Used Today?

Source: The Mine Foreman's Handbook by Robert Mauchline - 1910, Google Books

No, the Davy lamp is no longer used in modern mining. It has been replaced by electric lamps and advanced gas detectors, which are safer, brighter, and more accurate. Open flames are now banned in mines, and strict safety regulations require better tools. Today, the Davy lamp is mainly seen in museums or used symbolically in mining heritage events.

How Many Lives Did the Davy Lamp Save?

The Davy lamp is estimated to have saved thousands of lives during the 19th century. Some sources credit it with cutting mining deaths by over two-thirds in the decades following its introduction. Fatalities per million tons of coal dropped significantly after its introduction.

Parliamentary Reports on Safety Lamp Limitations

Despite the initial success of the Davy lamp, several official reports later criticized its overuse. A House of Commons Select Committee in 1835 found that the lamp gave owners confidence to mine dangerous seams without improving ventilation. Investigations after fatal accidents in places like Wallsend and Whitehaven showed that the lamps were often damaged, poorly maintained, or misused. Committees recommended better airflow systems, not just reliance on lamps, as the long-term solution to mine safety.

Negative Consequences of the Davy Lamp

The Davy lamp saved lives but also had downsides. It gave mine owners confidence to push into deeper, riskier seams and sometimes delayed better ventilation practices. In high gas concentrations, the lamp could extinguish, leaving miners in darkness just before danger struck. It reduced accidents but also encouraged riskier mining.

Davy Lamp Drawings

Source: Mining an Elementary Treatise on the Getting of Minerals by Arnold Lupton, M.I.C.E, F.G.S., etc. - 1896,. Google Books

Was It Davy or Stephenson Who Invented the Lamp

George Stephenson demonstrated his own safety Geordie lamp design at Killingworth Colliery in October 1815, a few weeks before Davy’s public presentation. His version used a glass chimney and controlled airflow. While the two lamps differed in method, their timing sparked a long-standing dispute over who deserved credit.

Source: Young Chemists And Great Discoveries - 1939, Google Books

In the rivalry between Humphry Davy and George Stephenson over the invention of the safety lamp, older accounts make it clear that Davy's came first, developed in late 1815 after a request from the Rector of Bishopwearmouth. These sources emphasize that while Stephenson also created a working design around the same time, his approach was more empirical — that of a skilled engine-wright — whereas Davy’s lamp was the result of deep scientific reasoning and chemical experimentation. The two lamps were based on different principles: Stephenson’s used controlled air inlets and a glass chimney; Davy’s relied on wire gauze to arrest flames.

Source: Google Books

Older sources also highlight Davy’s refusal to patent the invention, choosing instead to offer it freely to protect miners’ lives. In recognition, he received silver plate, a Russian vase, and a baronetcy — symbols of both gratitude and the impact of his work. For Davy, this was science in service to humanity, not profit.

What Is the Difference Between a Davy Lamp and a Geordie Lamp?

Source: Google Books

| Feature | Davy Lamp | Geordie Lamp |

|---|---|---|

| Inventor | Humphry Davy | George Stephenson |

| Shielding | Brass wire gauze | Glass chimney with air tubes |

| Strength | Very robust | Delicate glass can break |

| Light | Dimmer | Brighter |

| Safety Mechanism | Flame cannot pass through fine wire gauze, preventing explosions | Air enters through narrow tubes; flame extinguishes if gas enters |

| Use in Practice | Widely adopted in many mines across Britain and abroad | Mainly used in the North East of England, especially Stephenson's own region |

Legacy of the Davy Lamp

Source: Young Chemists And Great Discoveries - 1939, Google Books

The Davy lamp stands as a landmark of applied science saving lives. Its invention marked a turning point in industrial safety, especially in coal mining. Though eventually replaced by electric lamps, it laid the groundwork for modern mine safety standards and became a powerful symbol of how scientific thinking could solve real human problems. Today, original Davy lamps are treasured by collectors and museums alike.

Share this article