Miners Lamp

It took just over 70 years to go from a flame enclosed in gauze to a portable electric lamp with a built-in battery — but more than 100 years for open flame lamps to fully disappear from mines.

From open flames to electric helmets — this timeline walks you through the key inventions, breakthroughs, and safety laws that shaped the evolution of miners’ lamps over two centuries.

Table of Contents

What Was The Problem of Mine Illumination?First Attempts at a Miners Lamp – Spedding’s Steel MillEarly Development of Safety LampsHistoryVariants of Miners’ Lamps Across HistoryComparison of Mining LampsWhat are the lights on a miner's hat called?What are the lights in mines called?Are miner's lamps safe?Why did miners use carbide lamps?How long does a miner's lamp last?What is used in miners lamp?What is a miner's lamp called?What Was The Problem of Mine Illumination?

Dim light and firedamp explosions made mining deadly.

Early miners worked by candlelight, but there is no reflection of light on the black walls of the mine, leaving only a faint glow about ten feet across. As mines went deeper, open flames from candles or oil lamps became dangerous in the presence of methane gas, or “firedamp,” where even a spark could cause a fatal explosion.

First Attempts at a Miners Lamp – Spedding’s Steel Mill

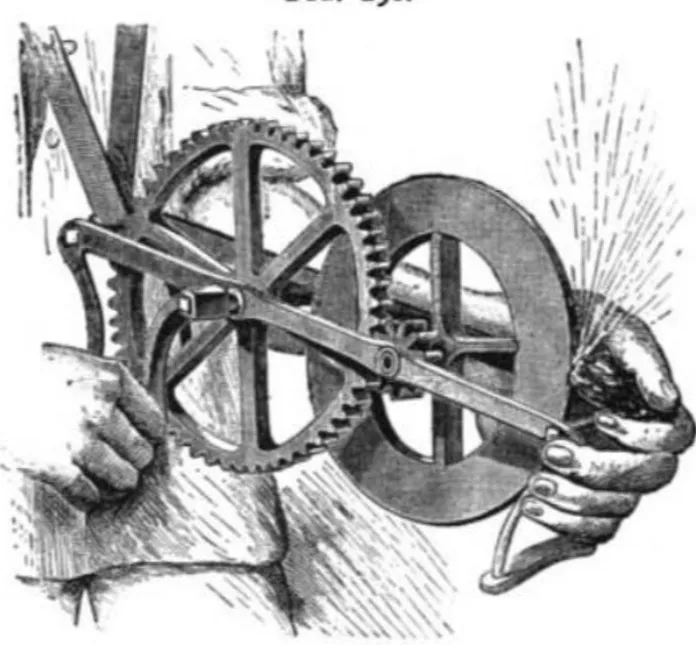

Fire damp explosions were the miner’s deadliest enemy in the 18th century, driving the search for brighter, wider light without the danger of an open flame.

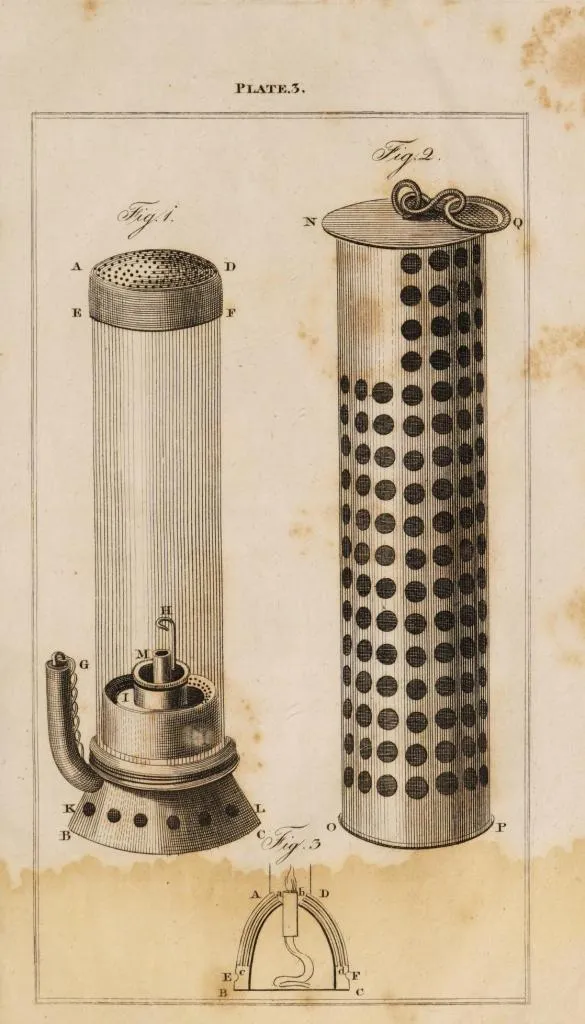

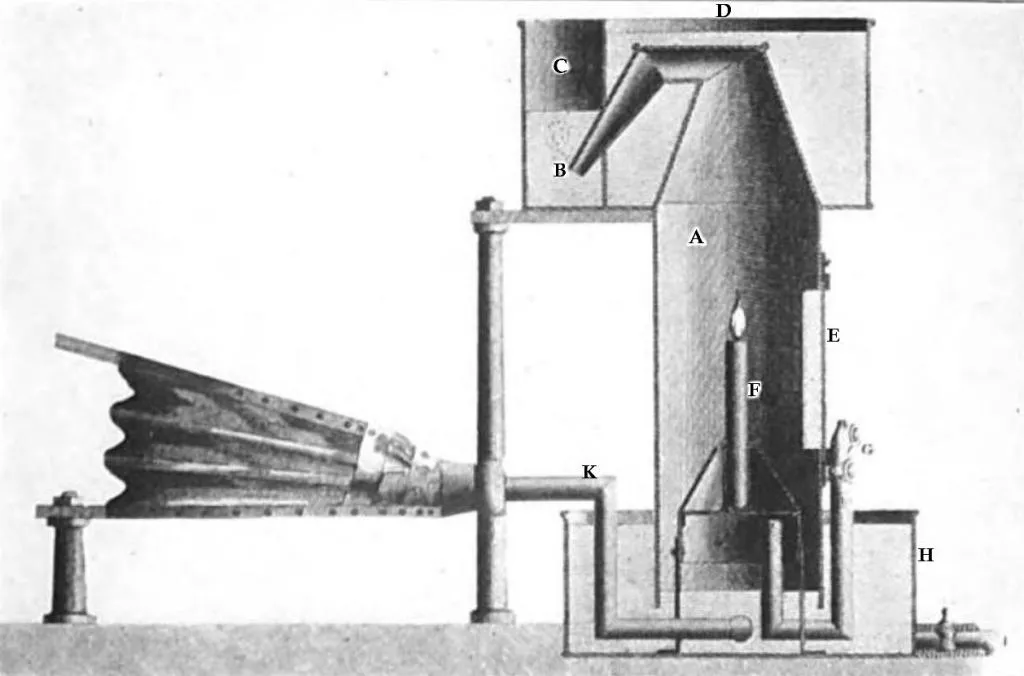

Source: Mine Gases and Explosions by J. T. Beard, C.E., E.M., 1908 - Google Books

In the mid-18th century, poor candlelight and explosive fire damp made mining both dim and deadly. Spedding sought a safer source of illumination and invented the steel mill — a hand-cranked device that produced a shower of sparks bright enough to light a larger area than a candle, without using a naked flame. Though safer in theory, it still carried risks, and in 1755 Spedding himself was killed in a gas explosion.

Early Development of Safety Lamps

In the early 19th century

- Dr. William Reid Clanny (1776–1850),

- Sir Humphry Davy (1778–1829),

- George Stephenson (1781–1848), and

each worked independently to design a lamp that could be used safely in coal mines. They lived at the same time but developed their ideas separately, contributing key features that shaped later safety lamps.

Vintage Oil Lamp British Coal Miners Company Wales Paraffin Miners Lantern with Hook

History

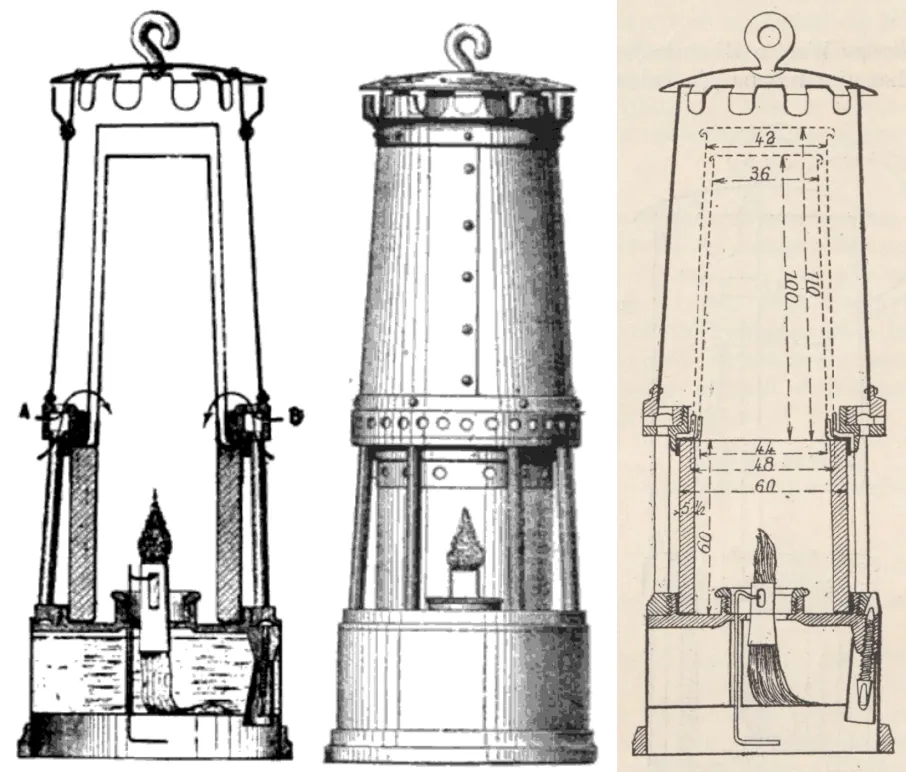

1813 – Dr. Clanny Designs the First Flame Safety Lamp for Mining

Clanny was undoubtedly the first to design a closed-flame lamp, and the first to build a lamp and to have it actually tested underground in a gaseous atmosphere. According to his statement in 1815, his first model was made about 1811. In 1813, he sent a paper to the Royal Philosophical Society, with drawings of a lamp.

Source: Department of the Interior, Bureau of Mines, Production and Briquetting of Carbonized Lignite by E. J. Babcock and W. W. Odell, 1923 - Google Books

- Key Feature: Combines glass cylinder and water seal or bellows (in early versions).

- How it Works: Air enters through water or filters, and the flame is enclosed in glass, improving visibility and shielding it from drafts.

Safer than early lamps, better visibility than Davy’s.

More complex and heavier.

1815 – Humphry Davy Develops the Wire-Gauze Flame Safety Lamp

Davy’s lamp allowed light into the mine without letting flame escape into dangerous gases.

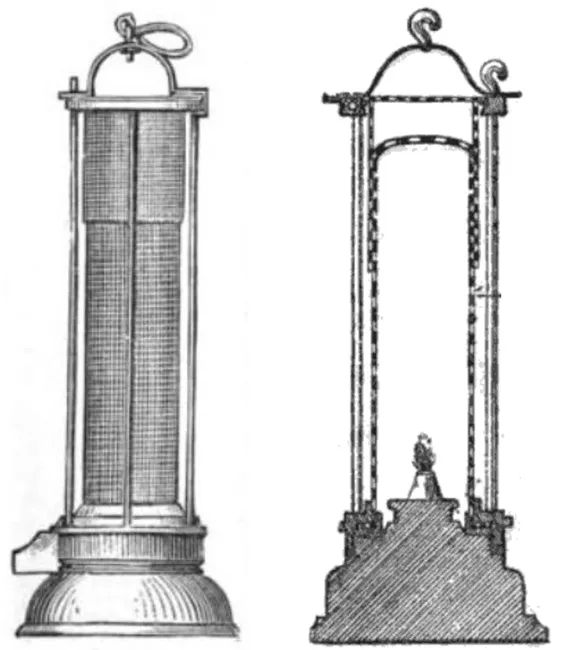

Source: Mining - An elementary treatise on the getting of minerals by Arnold Lupton, M.I.C.E., F.G.S., ETC., 1896 – Google Books

- Key feature: Fine iron wire gauze around the flame.

- How it works: The gauze cools the flame, preventing it from igniting flammable gases outside the lamp.

Simple, effective in many cases.

Flame could still pass through if the gauze was damaged or airflow was too strong.

Learn More Still qurious? Click here to learn about the Davy lamp.

1815 – George Stephenson Introduces the Geordie Safety Lamp

Stephenson’s Geordie lamp cut off its own flame when gas levels became dangerous, offering miners both light and a warning system.

Source: Samuel Smiles - Lives of the Engineers, 1862, Google Books

- Key feature: Perforated metal plate (not gauze), tight-fitting parts, and restricted air inlets.

- How it works: Carefully controlled airflow enters below the flame; top part cools gases before they can exit.

Stronger and safer than Davy’s in high-velocity air.

Airflow restriction could make the flame unstable.

Learn More Still qurious? Click here to learn about the Geordie lamp.

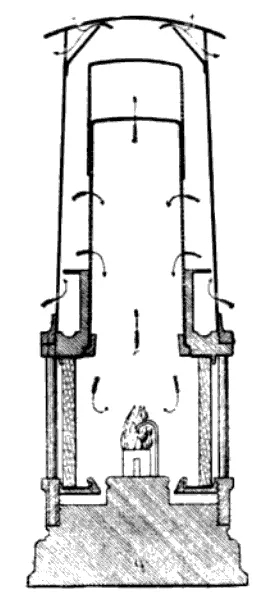

1840 – Mathieu Mueseler Introduces the Mueseler Safety Lamp in Belgium

The Mueseler lamp’s chimney design and protective bonnet made it one of the few flame lamps still considered safe in high-velocity mine air.

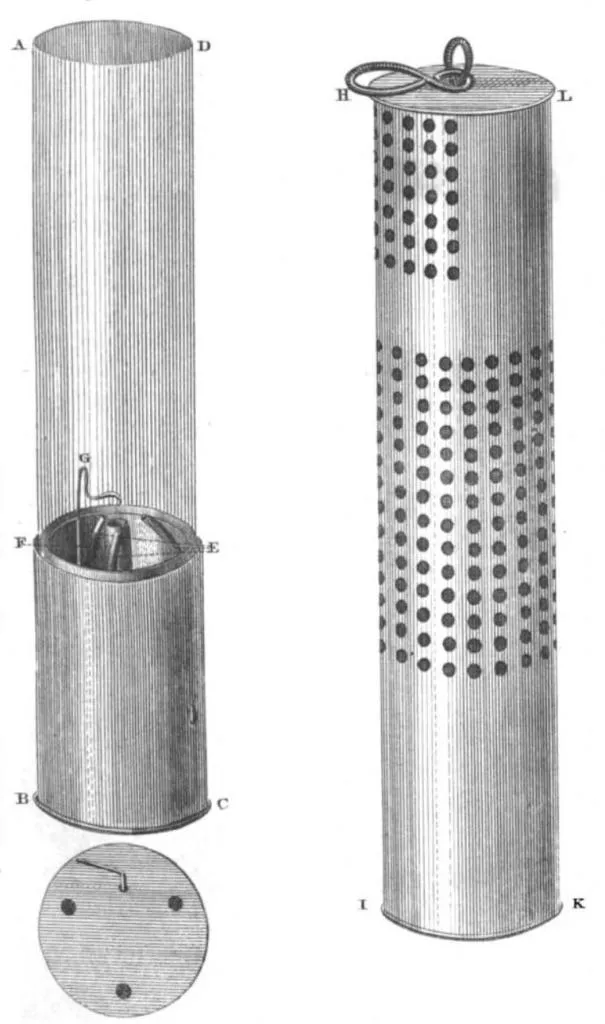

Source: Google Books, Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF)

- Key Feature: Vertical chimney (tube) above the flame to improve airflow and flame stability.

- How it Works: Enhanced chimney effect ensures better air circulation, stabilizing the flame and reducing risk of internal explosion.

Much safer — better at preventing flame propagation and extinguishes if dangerous gases are present.

Cannot be tilted safely; complex structure increases maintenance and risk of misuse underground.

Paraffin Lamp British Coal Miners Company Wales UK Aberaman Colliery Oil Lantern with Hook

1870s – J.B. Marsaut Improves Safety Lamp with Double Gauze Design

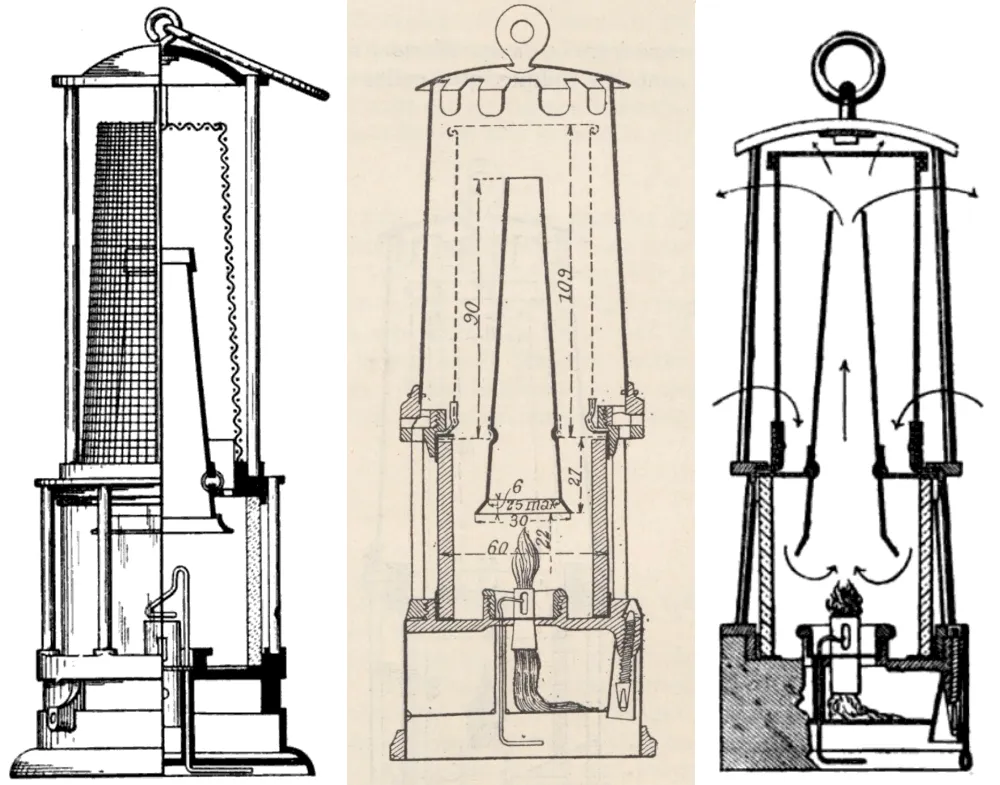

The Marsaut lamp added layered flame protection with multiple gauzes, making it safer in harsh and explosive conditions.

Source: Google Books, Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF)

- Key Feature: Double or triple wire gauze cylinders around the flame, often enclosed in a bonneted metal case.

- How it Works: Each gauze layer blocks heat transfer from flame ignition inside the lamp. If the inner gauze fails or overheats, outer layers remain cool enough to stop flame propagation.

Highly resistant to internal ignition and mechanical damage; remains safe even if one or two gauzes are compromised.

Reduced brightness; can clog with dust in unbonneted models; airflow conflict may cause smoking or flame instability.

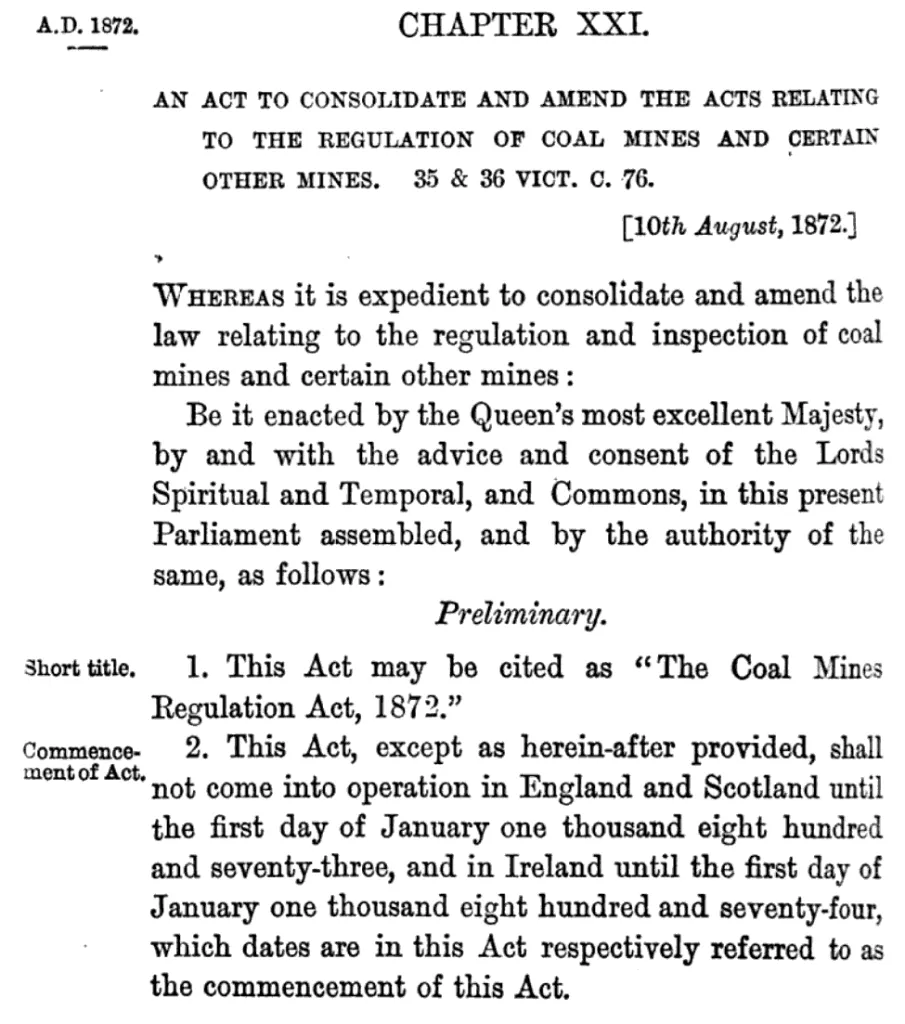

1872 – Coal Mines Act Requires Locked Safety Lamps in Hazardous Conditions

Source: Google Books

The 1872 Coal Mines Regulation Act required that in mines where firedamp (methane) was likely to be present, only locked safety lamps could be used, and they had to be kept locked while underground so miners couldn’t open them to expose a naked flame.

1881 – Joseph Swan Demonstrates the First Practical Electric Mine Lamp

This early electric lamp marked the transition from flame to filament in underground lighting.

Source: by Stable MARK - own work

- Key Feature: Sealed electric bulb housed in a protective glass and metal casing.

- How it Works: Electricity powers a filament inside the bulb, producing light without flame.

No risk of igniting gas; stable light output; better visibility underground.

Required external power source or battery; fragile glass components; limited early adoption in mines.

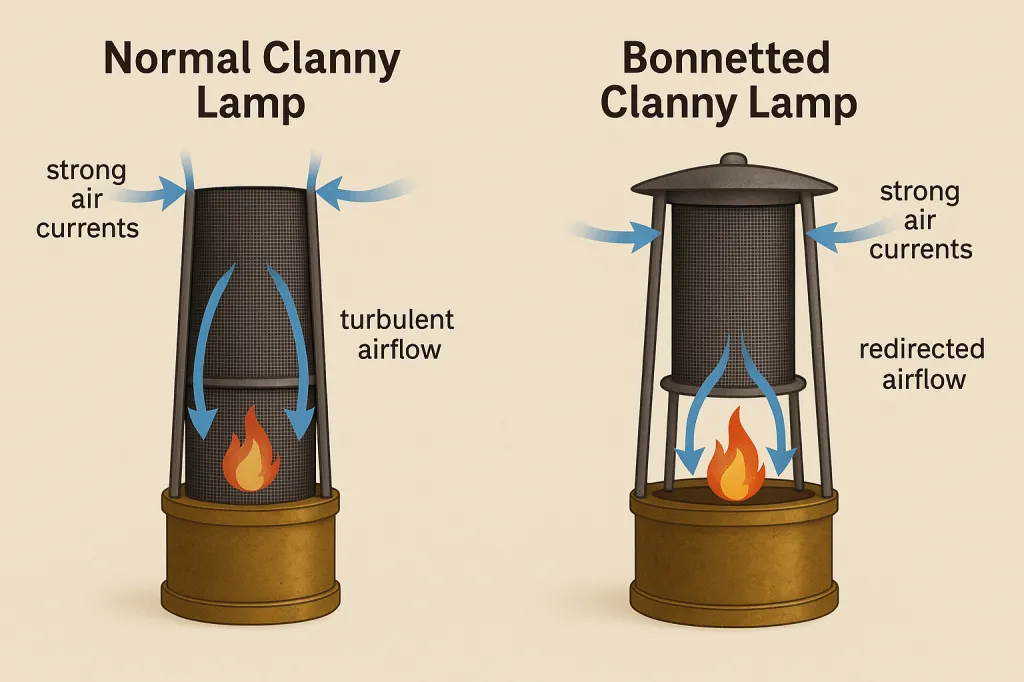

1882 – William Reid Clanny Adds Bonnet to Improve Lamp Stability

As mine ventilation improved for safety against gas accumulation, it ironically created a new hazard for flame lamps — and the bonnet was the solution to keep the flame contained in those harsher conditions.

Source: AI generated diagram

- Key Feature: Protective metal bonnet fitted over the top of the lamp.

- How it Works: The bonnet shields the gauze and flame from strong air currents created by improved mine ventilation.

Prevents flame instability and accidental ignition in fast-moving air.

Slightly heavier; reduced airflow can affect brightness.

1885 – Evan Thomas of Aberdare Produces a Clanny-Type Safety Lamp

Source: Groves and thorp's chemical technology or chemistry applied to arts and manufactures, Vol. II. By E. J. MILLS, D.Sc., F.R.S., and F. J. ROWAN, C.E. 1895, Google Books

- Key Feature: A Clanny-type safety lamp redesigned for greater strength and stability in high-ventilation mines.

- How it Works: Retains the glass cylinder and gauze principle of the Clanny lamp but uses sturdier construction and improved airflow shielding to keep the flame stable under strong air currents.

More durable, safer in turbulent ventilation, better suited for late 19th-century deep mines.

Heavier than standard Clanny designs.

Evan Thomas later merged with Williams to form E. Thomas & Williams Ltd., which went on to become one of the world’s most renowned miners’ lamp manufacturers.

Learn More Still qurious? Click here to learn about the E. Thomas & Williams Ltd..

1886 – Royal Commission Tests Safety Lamps and Issues Recommendations

In 1886, the Royal Commission on Accidents in Mines tested safety lamps and recommended stronger protection against air currents, better locking mechanisms, and improved gauze durability.

1887 – Coal Mines Act Sets Standards for Safety Lamp Design and Use

In 1886, the Royal Commission on Accidents in Mines tested safety lamps and recommended stronger protection against air currents, better locking mechanisms, and improved gauze durability.

1889 – John Davis & Co. of Derby Supplies Portable Electric Lamps for Mining

Source: The Mining Journal, 11 Sep 1891, Google Books

- Key Feature: Portable electric lamp removing the need for a flame.

- How it Works: Battery-powered light source in a durable casing, safe in gas-rich environments.

No ignition risk from flame, brighter and steadier light.

Early models were heavy and had limited battery life.

1909 – Cap Lamps Introduced for Hands-Free Illumination in Scottish Mines

Source: Investigations of Permissible Electric Mine Lamps, 1930-40, by L. C. Ilsley, A. B. Hooker, Etats-Unis. Mines (Bureau), W. H. Roadstrum - 1942, Google Books

- Key Feature: Cap-mounted miners’ lamp attached to helmet for hands-free lighting.

- How it Works: Light fixed to headgear, often powered by a cable to a waist- or belt-mounted battery pack.

Frees hands, light follows line of sight, improves mobility and safety.

Early versions could be heavy and had limited battery duration.

1920 – Electric Safety Lamps with Built-In Accumulators Debut in Mining

Source: Investigations of Permissible Electric Mine Lamps, 1930-40, by L. C. Ilsley, A. B. Hooker, Etats-Unis. Mines (Bureau), W. H. Roadstrum - 1942, Google Books

- Key Feature: Self-contained electric safety lamp with a built-in rechargeable accumulator (battery).

- How it Works: Lamp and battery are housed together, removing the need for an external battery pack or cable.

More portable, fewer parts to maintain, no flame hazard, consistent light output.

Early accumulators were heavy and required frequent recharging.

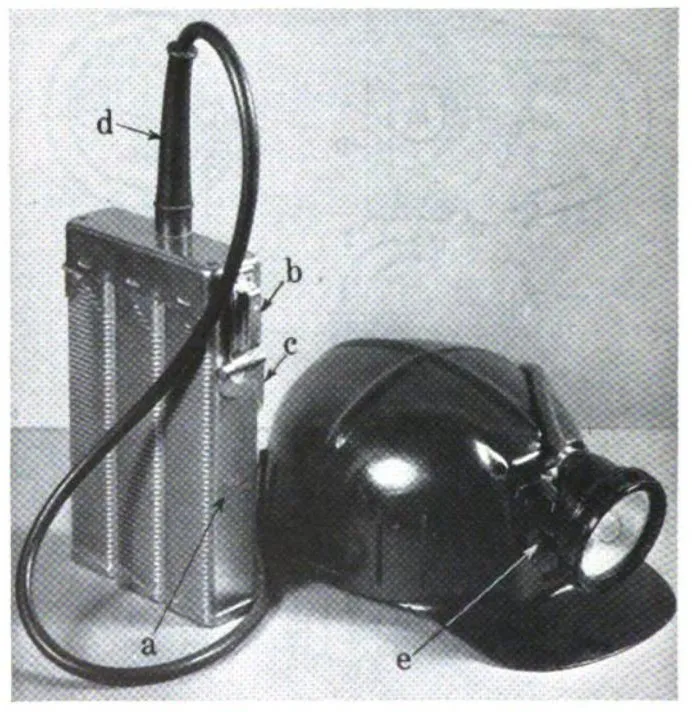

1950 – Electric Safety Cap Lamp with Battery Pack by Concordia, Cardiff

Source: Google Books

- Key Feature: Electric safety cap lamp paired with a separate belt-mounted battery pack.

- How it Works: Lamp mounted on helmet, powered by a cable from a rechargeable battery worn on the miner’s belt.

Safer than flame lamps, bright and steady light, weight kept off the helmet.

Battery packs could be bulky and needed regular charging.

Variants of Miners’ Lamps Across History

- Open flame lamps – early oil, oil-wick or candle lamps, very unsafe in gas-filled mines.

- Safety lamps – Davy, Geordie, Clanny, Mueseler, Marsaut, and later bonneted or improved types using gauze, glass, or chimneys to contain the flame.

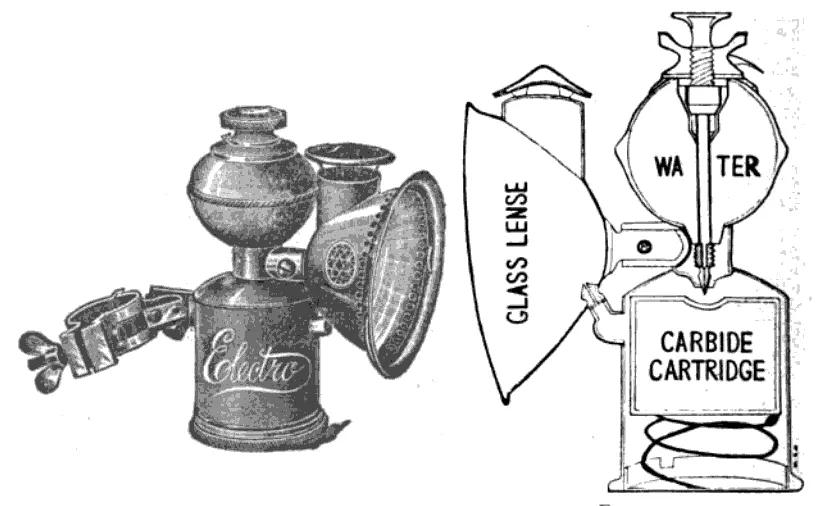

- Carbide lamps – used calcium carbide to produce acetylene gas for a brighter flame (popular 1900–1930s).

Image: Carbide miner’s lamp with diagram showing how water drips onto calcium carbide to generate acetylene gas for a bright flame.

Source: The C.T.C. Gazette, December 1898, Google Books - Electric lamps – first introduced in the mid-19th century, later with built-in accumulators or separate battery packs.

- Cap lamps – helmet-mounted lamps, first with carbide, later with electric power packs, and today with lightweight rechargeable LEDs.

- Wheat lamps – durable and reliable electric cap lamps developed in the 20th century, typically with a belt-mounted battery pack, widely used in U.S. coal mines.

Image: Super-Wheat (WTA) electric cap lamp : It is widely used and is with separate battery pack, produced by Koehler Manufacturing Co., USA.

Source: Google Books

Comparison of Mining Lamps

| Lamp | Year | Type | Shield/Structure | Airflow Design | Visibility | Safety Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clanny | 1813 | Flame | Glass + gauze | Water or filtered intake | Good | High |

| Davy | 1815 | Flame | Iron wire gauze | Passive through gauze | Low | Moderate |

| Stephenson | 1815 | Flame | Metal plate + sealed joints | Restricted inlets | Moderate | High |

| Mueseler | 1840 | Flame | Glass + gauze + chimney | Draft-enhanced airflow | Good | Very High |

| Clark Electric | 1859 | Electric | None (no flame) | Not applicable | Very High | Revolutionary |

| Marsaut | 1870s | Flame | Double gauze + glass | Improved shielding + flow | Fair | Very High |

| Bonnetted Clanny | 1882 | Flame | Glass + gauze + bonnet | Redirected ventilation | Good | Very High |

| Thomas | 1885 | Flame | Sturdy Clanny-type with glass + gauze | Improved shielding for high ventilation | Good | Very High |

| Electrical Accumulator Lamp | 1920 | Electric | Self-contained lamp with built-in battery | No external battery needed | Good | Very High |

| Concordia Electric Cap Lamp | 1950 | Electric | Cap lamp with belt-mounted battery pack | Cable from belt pack to helmet lamp | Very Good | Very High |

What are the lights on a miner's hat called?

Early versions were often carbide lamps mounted on a bracket at the front of the helmet, used from around 1900 to the 1930s, producing light by burning acetylene gas. Modern cap lamps are usually LED units with rechargeable batteries, giving bright, hands-free light underground.

What are the lights in mines called?

The lights in mines are called cap lamps or helmet lamps when worn on a miner’s helmet, and safety lamps when referring to the older flame-protected designs. In a broader sense, underground lighting systems are simply called mine lights.

Are miner's lamps safe?

Modern miner’s lamps, especially LED and approved electric safety lamps, are very safe as they produce no flame. Historic flame safety lamps were safer than open flames but still carried some risk if damaged, poorly maintained, or used in strong air currents.

Why did miners use carbide lamps?

Miners used carbide lamps because they produced a bright, steady flame by reacting calcium carbide with water to make acetylene gas. They were cheap, portable, and brighter than oil lamps, making them popular before electric lamps became widespread.

How long does a miner's lamp last?

The runtime of a miner’s lamp depends on its type:

- Historic oil safety lamps: about 8–24 hours before refuelling.

- Carbide lamps: typically 4–8 hours per fill.

- Modern LED cap lamps: often 12–36 hours on a single battery charge.

What is used in miners lamp?

Historically, miners’ lamps used oil, paraffin, or calcium carbide as fuel for a protected flame inside a safety lamp.

What is a miner's lamp called?

A miner’s lamp is commonly called a safety lamp, used to light mines while preventing explosions from flammable gases. Famous types include Davy’s Lamp (1815, using wire gauze to enclose the flame) and the Geordie Lamp (Stephenson’s design, using restricted airflow and metal shielding).

Share this article